Just because a story has been brilliantly told does not make it unworthy of a revisit now and again.

This is particularly so when the tale—told in Mark Bowden’s book Black Hawk Down and the movie based on it—engenders so many of the characteristics that have made our country great, and our nation’s service members, with few exceptions, beyond compare. It is not merely a heroic undertaking in the face of terrible odds, it’s a testament to the “guy next to you” ethic of combat, even when that guy is someone you do not know. A good memory and an eye to the calendar may tip our hand, but if not: 22 years ago this week, the Nation’s first Medals of Honor since Vietnam were earned in Mogadishu, Somalia.

In January 1991, coup-installed (1969) President Mohamed Siad Barre was overthrown. In the following months, increasingly severe fighting between “clans” would break out in and around Mogadishu. One of the first casualties was virtually all Somali agriculture. Rampant starvation and malnutrition followed, and in August President George H. W. Bush announced a U.S. military airlift to support the multinational UN relief effort. By February of 1993, more than 48,000 tons of food and medical supplies had landed in Somalia, but most (roughly 80 percent) was hijacked and sold or traded abroad to support the widening conflict. Clan kleptocracies were the only remnants of government.

By February of 1993 more than 48,000 tons of food and medical supplies had landed in Somalia, but most was hijacked and sold or traded abroad.Aid workers were under nearly constant threat. Just prior to leaving office, President Bush authorized Operation Restore Hope, which provided combat-ready troops to protect the delivery of aid. By this time (December 1992/January 1993), half a million Somalis had died, and another 1.5 million were refugees or otherwise displaced. Success on many fronts was mixed, while inter-clan strife escalated.

A March conference seemed to set terms for peace and the restoration of democratic government. Though a signatory to the agreement, the Somali National Alliance—led by clan chief, warlord, Army General, former Indian Ambassador and Somali Intelligence Chief Mohamed Farrah Aidid—thwarted the Agreement’s implementation. A seesaw chase of Aidid took place through the month of July, with a raid missing him at a safe house. Reprisals followed that took the lives of four U.S. soldiers in one attack and injured seven others in a second. Four journalists were killed by a mob on July 12.

Amid mounting tensions, President Bill Clinton approved the deployment of Task Force Ranger to Somalia in late July. Reaching Mogadishu on Aug. 22, it included a diverse complement of U.S. Army Rangers (B Company, 3rd of the 75th) and Delta Force (C Squadron, 1st SFOD-D), Navy Seals (DEVGRU), and Air Force Pararescuemen and Combat Controllers (24th STS), with air support from the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment. Major General William F. Garrison, JSOC Commander, was also in command of the task force.

Aidid continued to prove elusive. The capture of his financier Osman Ali Atto on Sept. 21 provided only limited intelligence. On Sept. 25, the stakes went up yet again with the downing of a 101st Airborne Black Hawk and the loss of three crewmen. Another close advisor of Aidid’s was sought for intelligence, and just after noon on Oct. 3, intelligence sources identified the location of the Habar Gidir warlord’s Foreign Minister Omar Salad Elmi and top political advisor Mohamed Hassan Awale. The informant even suggested the possibility that Aidid might be present for the meeting at the Olympic Hotel in the heart of Habar Gidir territory: Bakara Market.

This was the cue for “Gothic Serpent,” Gen. Garrison and Task Force Ranger’s plan to capture key clan leaders, despite the perilous location. In the broad strokes, it was a good plan: With target individuals in a known location, the 160th’s AH-6 “Little Birds” would ferry Delta to the building. Fast roping to the roof, Delta operators would take the building top-down, identifying and securing targets as they went.

Outside, four Ranger “chalks” would fast rope from UH-60 “Black Hawks” to secure the perimeter. A column of Humvees and Army flatbed trucks would arrive shortly thereafter to exfil the assault force and any detainees back to the Task Force Ranger HQ at the Mogadishu Airport.Almost from the outset, the planned half-hour expedition “went south.”

Almost from the outset, the planned half-hour expedition “went south.” One Ranger fell 70 feet to the ground. Another UH-60 found itself a block off target with its perimeter-defense chalk. The convoy was delayed in the tight confines of Mogadishu streets, alternately clogged or out-and-out barricaded by residents against both UN forces and rival clans.

Forty minutes in, an RPG claimed Black Hawk “Super 61.” Both pilots were killed in the crash. Air Force Pararescuemen lead by TSGT Scott Fales were able to rescue the remaining wounded crewman. Two Delta snipers (SSG Daniel Busch and SGT Jim Smith) had survived the crash and were defending their comrades against withering small arms fire. Little Bird “Star 41” nevertheless landed to extract the Delta operators, while other Rangers and Deltas arrived to secure the crash site. SSG Busch unfortunately died of his injuries, having been shot four times defending his comrades.

Communications problems and delays to the convoy would prove even more costly when an RPG hit a second orbiting Black Hawk—“Super 64.” Like ’61, ’64 went down hard. Pilot Mike Durant (CWO3) was pinned in his seat with a crushed vertebra and compound fracture of his left femur; in the end, he would be the only survivor of Super 64.

Nearby “Super 62” carried Delta snipers MSG Gary Gordon and SFC Randy Shughart, who twice asked to be inserted at the ’64 crash site. Their command refused, citing what they (correctly) believed was overwhelming danger: Surveillance revealed a large and hostile crowd of Somalis already massing around the crash site. A third request was reluctantly granted, and ’62 set Gordon and Shughart down approximately 100 yards from the wreckage of ’64.

While simultaneously defending the site, the Delta operators removed Durant and other crewmembers from the Black Hawk. Their staunch defense of their grounded comrades could not last long, though the attacking Somali militia paid dearly—Durant’s book In the Company of Heroes said militia dead numbered at least 25 in their fight with the Delta snipers.

While simultaneously defending the site, the Delta operators removed Durant and other crewmembers from the Black Hawk.Of the two, Gary Gordon was likely killed first (the official record reverses the order). Randy Shughart’s distinctive M14 was not the weapon Mike Durant ended up with, but rather Gordon’s CAR-15, brought to him by Shughart before the site was finally overrun.

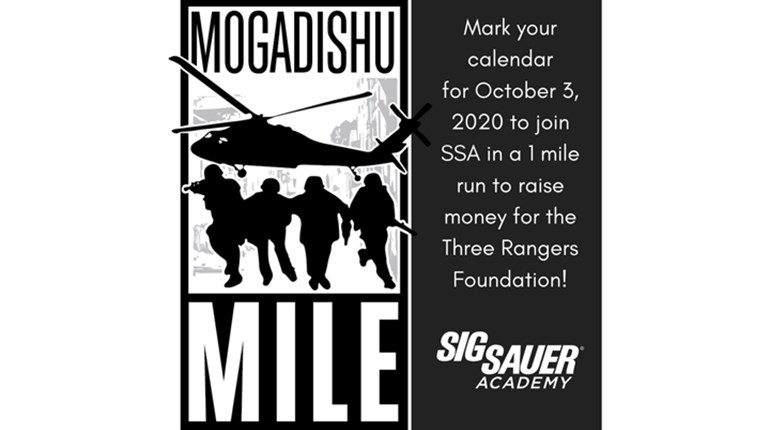

What’s been called “The Battle of Mogadishu” was far from over. Rangers and Delta would spend much of a harrowing night in a series of desperate firefights. Widely separated units would coalesce mainly around the first crash site, and by dawn more than 100 vehicles martialed by Gen. Garrison from the UN forces (Malaysia and Pakistan) and the 10th Mountain Division would carry most to safety. Even so, some combatants and their rescuers had to hoof it out when the vehicles were full (the Mogadishu Mile).

Casualties in Gothic Serpent are perplexing in retrospect (U.S.: 18 dead and 73 wounded), as it might easily have been much worse but for repeated heroics. Besides the posthumous Medals of Honor for Gordon and Shughart, one Air Force Cross and 41 Silver Stars were awarded for action that day. Opposing casualty counts vary wildly, ranging from 315 (dead) to 2,000 dead and wounded.

There were many lessons. While the mission itself was a success—high-ranking Aidid lieutenants were captured—the impacts and costs were almost certainly not a worthwhile exchange. U.S. troops were clearly under-supported. Armor and air cover were withheld from General Garrison for political reasons at deadly cost, though he still accepted full responsibility for the results, and doing so effectively ended his very distinguished career.

In the longer term, the aid mission to Somalia was also a failure. In a pattern oft (and recently) repeated, the U.S. would depart before the mission was completed with wasteful, deadly consequences. Also, there was a determined resistance to recognizing the involvement of al-Qaeda: Osama bin Laden would later use the incident for propaganda and recruiting purposes, and at least three al-Qaeda leaders were reported to have been present during, and participated in, the battle.

Black Hawk Down author Bowden summed it up in a 2013 NPR interview: “So we, by withdrawing from Somalia, left a lawless region ripe for al-Qaida and gave at least a whole generation of Somalis over to these Islamist fundamentalists to be educated and groomed.”