It is usual to think of George Washington as a soldier who became the president rather than as a farmer who happened to become a soldier. Yet when he took command of the Continental Army in July 1775, that is precisely what happened.

Washington knew this. The sum of his military experience consisted of a stretch in the 1750s when he was an unseasoned lad in his twenties commanding the Virginia militia in the Ohio wilderness. In the French and Indian War his men brought little more than pluck and buckskins to the job, and the British generals he served under—the doomed Edward Braddock and the competent John Forbes—provided bad and good lessons by example, but at the time Washington didn’t profit from this actual contact with practical events. He often let youthful resentments cloud his judgment and unjustified overconfidence blinker his eyes. Twenty years later, as he left Philadelphia to take command of the crowd being styled the Continental Army, he was older at 43 and wiser from his years spent managing a complex farming operation, but he remained woefully inexperienced in the art of war.But Washington as general never adopted the kind of prudence that would have become paralysis in a less certain man.

In fact, George Washington’s military deficiencies could have been the undoing of the patriot cause, and many historians have been quick to deride him for repeatedly jeopardizing his army and missing golden opportunities. They have also concluded that he survived only because his opponents were bumbling second-raters. Yet the assessment is unfair to British generals who were always competent and sometimes gifted. They had superior knowledge of established military forms and tested tactics, and they brought wide experience to a fight against a foe inferior in everything necessary for the game of maneuver and the challenge of combat. It isn’t difficult to see why even serious setbacks could not diminish their certainty that their way of war would win in the end. It had been tested for years against formidable foes arrayed in Europe, on the Plains of Abraham, and across the Indian subcontinent. The British never had the slightest doubt that they would quash the rebellious American rabble led by a Virginia farmer with the new and fancy title of “His Excellency.”

Washington was painfully aware of how little he knew, and he masked his insufficiency while spending long nights reading European military manuals and longer days asking questions of people he trusted. The farmer had already developed the habit of confronting problems with caution and deliberation, and it helped the general curb the impetuous streak of his youth. But Washington as general never adopted the kind of prudence that would have become paralysis in a less certain man. Because he was a diligent student of everything he undertook, George Washington brought to the impossible task of challenging the most powerful empire in the world a uniquely happy temperament for patience peppered by bold action. In the American setting and for the American time, it proved far more beneficial than the genius of a Napoleon.

Washington’s contribution as soldier was crucial in winning American independence, but the value of Washington the visionary in sustaining American liberty is immeasurable. In fact, it was the decisive factor in the turbulent years during and after the war. He understood the American Revolution better than any of its foes and, for that matter, many of its friends. His grasp of its meaning made him more than a military figure at the center of a world-changing event. It made him the exemplar of the American military ideal, a New World Cincinnatus who was a citizen first and last, and the bearer of arms only when his neighbors’ homes needed defending.

Friedrich von Steuben rewrote traditional drill manuals to transform highly individualistic men into a capable military organization, and over time Washington gained confidence in managing and moving an army. But he never forgot that the conflict at its heart was insurrectionary and consequently was a philosophical as well as martial contest. Success hinged on winning what modern strategists call “hearts and minds,” meaning not just the loyalty but the affection of a people buffeted by great change. Washington knew that men the people loved could more than match the legions, the expertise, and the will of those they feared. It was with that understanding that the farmer became a soldier out of necessity. And when flush with victory and fully in command of the people’s hearts as well as their army, he put down his sword and returned to his farm as a matter of choice.

It is hard to imagine anyone else in the world doing that. But America was not just any place in the world. Home again at last, George Washington strapped a lunch pail to his saddle and tugged on a broad-brimmed hat for the daily ride across his acreage. In fair seedtime, America would become the hope of the world. The soldier made it possible because the farmer had known it in his bones.

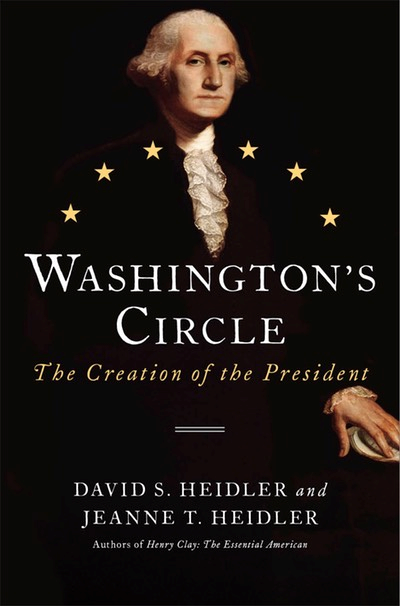

David and Jeanne Heidler have collaborated on numerous books about the early American republic, the Antebellum period and the Civil War. Their latest is Washington’s Circle: The Creation of the President.