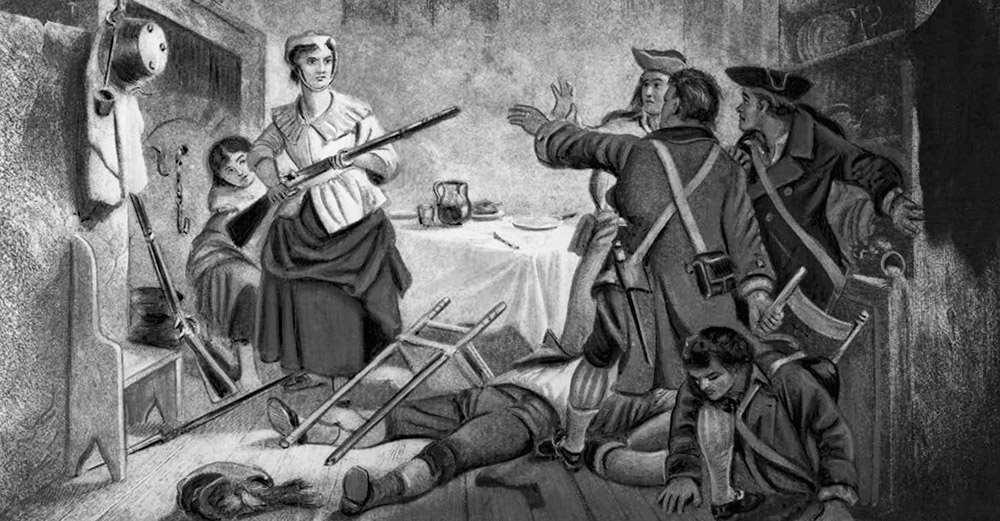

As this artist’s depiction shows, the American patriots who took up arms to fight for their freedom in 1775 and in the years after often did not have uniforms and, especially early on, brought their own guns to the fight.

We normally think of the British attempt to disarm the American colonists as beginning in 1775, when “the shot heard ‘round the world” was fired. That impression is understandable, as this was the first time American militiamen and British regulars actually did battle. Against all odds, the militia routed the Redcoats all the way back to Boston.

But that was hardly the beginning of the irreconcilable conflict between George III and the patriots in regard to what was considered the right of Englishmen to be armed. That conflict started in 1768, when ships with British forces were approaching Boston to put down resistance to taxation without representation, searches without warrants and the coercive acts imposed on the Americans.

According to The Boston Gazette (Sept. 26, 1768): “It is reported that the Governor has said, that he has Three Things in Command from the Ministry, more grievous to the People, than any Thing hitherto made known. It is conjectured 1st, that the Inhabitants of this Province are to be disarmed. 2d. The Province to be governed by Martial Law. And 3d, that a Number of Gentlemen who have exerted themselves in the Cause of their Country, are to be seized and sent to Great-Britain.”

When it was leaked that Massachusetts Colonial Gov. Francis Bernard had requested the troops, James Otis, Samuel Adams and other patriots orchestrated a stormy meeting of the townsmen at Faneuil Hall (which is still there today). A resolution was adopted recalling that the English Declaration of Rights of 1689 declared that “the Subjects being Protestants, may have arms for their Defence,” and admonishing every inhabitant to “always be provided with a well fix’d Firelock, Musket, Accouterments and Ammunition,” as the militia law required.

Seven hundred British infantrymen from Halifax, Nova Scotia, landed on October 1, taking over key points in Boston. They were quartered among the population. The hated standing army had arrived. It began its diabolical occupation of the town that would be a flash point for years to come. Other colonies protested with petitions to the Crown and Parliament.

British Gen. Thomas Gage then doubled the number of troops, but they were vastly outnumbered by the armed Americans. According to The Boston Evening Post (Nov. 21, 1768): “The total number of the Militia, in the large province of New-England, is upwards of 150,000 men, who all have and can use arms, not only in a regular, but in so particular a manner, as to be capable of shooting a Pimple off a man’s nose without hurting him.” (The legend of the American sharpshooter was already widespread, even though it was obviously exaggerated.)

In early 1769, it was reported “[t]hat the inhabitants had been ordered to bring in their arms, ... and that those in possession of any after the expiration of a notice given them, were to take the consequences.” While that was an unfounded rumor, it expressed a legitimate fear among the population that was confronted by bullying troops on a daily basis.

Clashes between soldiers and civilians came to a head in the Boston Massacre of March 5, 1770, when Redcoats shot and killed five townspeople and wounded six more. In the trial that followed, John Adams defended the soldiers, most of whom were acquitted on the ground of self-defense. But it was also established in the proceedings that the inhabitants were entitled to carry arms to protect themselves.

In his popular pamphlet Oration, upon the Beauties of Liberty (1772), which was “humbly dedicated” to the Earl of Dartmouth, Secretary of State for America and church minister John Allen warned that “you will find, my Lord, that the Americans will not submit to be Slaves, they know the use of the gun, and the military art, as well as any of his Majesty’s troops ... .”

In late 1773, patriots disguised as Mohawk Native Americans gathered at Boston harbor, boarded three vessels, and dumped 45 tons of tea into the ocean. They were “cloath’d in Blankets with the head muffled, and copper color’d countenances, being each arm’d with a hatchet or axe, and pair pistoles,” wrote Boston merchant John Andrews. Andrews had written two weeks before the Tea Party: “‘twould puzzle any person to purchase a pair of p----ls [pistols] in town, as they are all bought up, with a full determination to repell force by force.” (Acquiring guns in times of trouble didn’t start in 2020.)

“[Y]ou will find, my Lord, that the Americans will not submit to be Slaves, they know the use of the gun, and the military art, as well as any of his Majesty’s troops ... .”

Parliament responded to the Tea Party by enacting the Intolerable Acts, closing Boston harbor to trade. More troops were forcibly quartered in residents’ homes, Gen. Gage was appointed governor and the elected town selectmen were replaced by Crown-appointed counselors that patriots named the “Divan” after a despotic Ottoman institution.

In September 1774, “it was proposed in the Divan ... that the inhabitants of this Town should be disarmed, and that some of the new-fangled Counsellors consented thereto, but happily a majority was against it.” Had it passed, it was thought that “50,000 men from the Country (some of whom were on the march) [would have] appear’d for our Relief.”

To counter the colonists who were continuing to arm themselves at the source, Gen. Gage began seizing the powder houses where large quantities of black gunpowder were stored. By preventing merchants from withdrawing their gunpowder from the powder houses, Gage could reduce the ammunition available to the inhabitants. His troops also began to search for and seize arms being taken out of Boston to the countryside. This crackdown on gunpowder stirred up a hornet’s nest. Thousands of inhabitants came out and protested.

In October 1774, “the King’s most excellent Majesty in Council” decreed a ban on the export of gunpowder and arms to America, and the British navy halted the importation of arms and ammunition into the colonies. An anonymous patriot wrote in The New Hampshire Gazette: “Whether, when we are by an arbitrary Decree prohibited the having Arms and Ammunition by Importation, we have not by the Law of Self Preservation, a Right to seize upon all those within our Power, in order to defend the Liberties which GOD and Nature have given us ... ?” (Dutch ships helped the Americans evade the embargo.)

The General Committee, South Carolina’s patriotic governing body, found that “by the late prohibition of exporting arms and ammunition from England, it too clearly appears a design of disarming the people of America, in order the more speedily to dragoon and enslave them; it was therefore recommended, to all persons, to provide themselves immediately, with at least twelve and a half pounds of powder, with a proportionate quantity of bullets.”

By now the Redcoats had instituted a general policy of searching for arms and seizing them. This induced the populace to arm themselves even more. An address from Worcester County presented to Gen. Gage complained: “This County are constrained to observe, they apprehend the People justified in providing for their own Defense, while they understood there was no passing the [Boston] Neck without Examination, the Cannon at the North-Battery spiked up, & many places searched, where Arms and Ammunition were suspected to be; and if found seized; yet as the People have never acted offensively, nor discovered any disposition so to do, as above related, the County apprehend this can never justify the seizure of private Property.”

Lord Dartmouth urged Gen. Gage in a letter dated October 17, 1774, to consider “disarming the Inhabitants of the Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut and Rhode Island,” but “it certainly is a Measure of such a nature as ought not to be adopted without almost a certainty of success ... .” Gage responded, “Your Lordship’s Idea of disarming certain Provinces would doubtless be consistent with Prudence and Safety, but it neither is nor has been practicable without having Recourse to Force, and being Masters of the Country.”

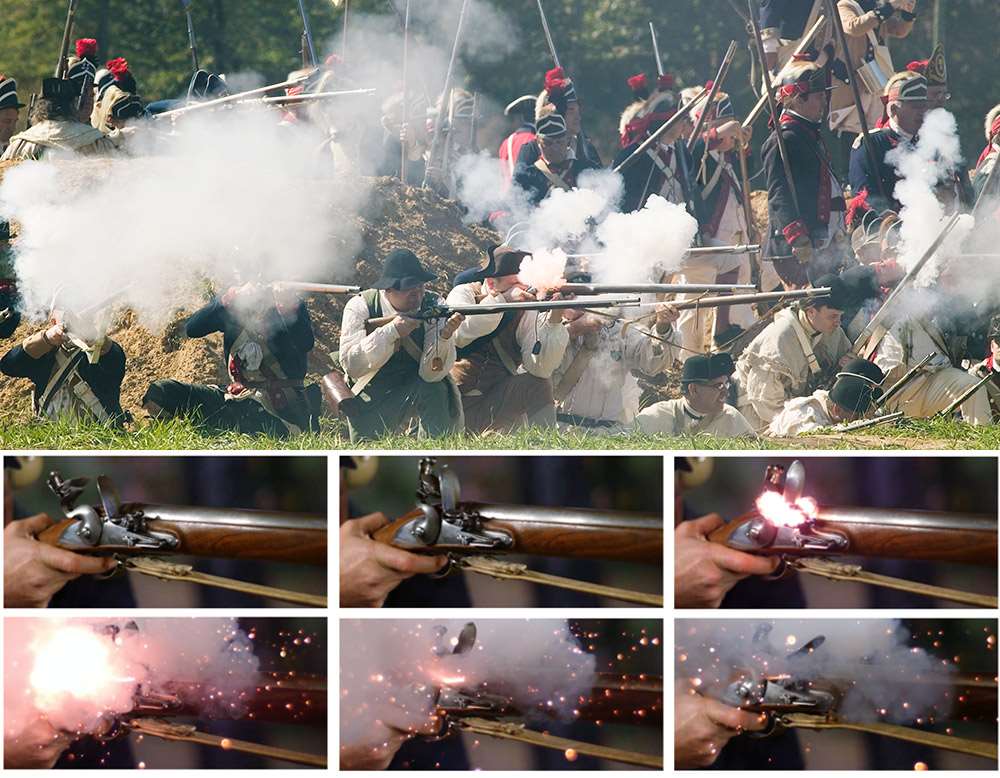

The patriots sought to intimidate the British with talk about the colonists’ expertise with arms. A pamphlet printed throughout the colonies and even in England credited with convincing the British of this expertise was written by Charles Lee, who was influential in the Continental Congress. A key passage states: “The Yeomanry of America have, besides infinite advantages, over the peasantry of other countries; they are accustomed from their infancy to fire arms; they are expert in the use of them: Whereas the lower and middle people of England are, by the tyranny of certain laws, almost as ignorant in the use of a musket, as they are of the ancient Catapulta.”

The Americans were arming themselves for what they considered to be just resistance to tyranny. Peter Oliver, a prominent Tory and former Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Superior Court, recalled: “The People began now to arm with Powder & Ball, and to discipline their Militia. Genl. Gage, on his Part, finding that Affairs wore a serious Aspect, made Preparations for Defence.” He added, “The People were continually purchasing Muskets, Powder & Ball in the Town of Boston, & carrying them into the Country; under the Pretence that the Law of the Province obliged every Town & Person to be provided with each of those Articles.”

As noted in the Jan. 31, 1775, diary entry of Lt. Frederick MacKenzie of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, “the people are evidently making every preparation for resistance. They are taking every means to provide themselves with Arms; and are particularly desirous of procuring the Locks of firelocks, which are easily conveyed out of town without being discovered by the Guards.”

Gage perceived and foretold a great decentralized force of American marksmen waging guerrilla warfare, which would be most difficult to repress. He wrote to Dartmouth on March 4, 1775: “The most natural and eligible mode of attack on the part of the people is that of detached parties of bushmen who from their adroitness in the habitual use of the firelock suppose themselves sure of their mark at a distance of 200 rods. Should hostilities unhappily commence, the first opposition would be irregular, impetuous, and incessant from the numerous bodies that would swarm to the place of action, and all actuated by an enthusiasm wild and ungovernable.” (He may have meant 200 yards, as 200 rods would be 1,100 yards.)

While Massachusetts took the center stage, the other colonies were preparing for the worst. Patrick Henry’s “liberty or death” oration on March 23, 1775, to the Convention of Delegates of Virginia in Richmond directly confronted the political import of an armed versus a disarmed populace. Henry implored: “They tell us ... . that we are weak [and] unable to cope with so formidable an adversary. But when shall we be stronger? ... Will it be when we are totally disarmed, and when a British guard shall be stationed in every house? ... . Three million people, armed in the holy cause of liberty ... are invincible by any force which our enemy can send against us.”

By now, Gen. Gage had stepped up the seizure of arms and ammunition that citizens were transporting from Boston to the countryside. Militia companies were organizing and exercising with arms. For Gage, the time had come to strike. On April 19, the armed colonists clashed with British regulars at Lexington and Concord. The rest is history.

The above is only a sampling of the events described in detail in my book The Founders’ Second Amendment. As we approach the 250th anniversary of our Declaration of Independence, consider how consistently the American people have exercised their right to keep and bear arms and how they have resisted attempts to confiscate their firearms. Reflecting that legacy, Congress has time and again rejected proposals to register firearms and even enacted laws prohibiting firearm registration. We have had our political equivalents to the Crown and the General Gages, but they have been no more successful than their colonial counterparts. It is truly time to celebrate America and its Second Amendment.

Attorney Stephen P. Halbrook is a senior fellow with the Independent Institute. His latest books are America’s Rifle: The Case for the AR-15 and The Right to Bear Arms: A Constitutional Right of the People or a Privilege of the Ruling Class? See, stephenhalbrook.com.